Will The Sunrise Again?

by Bill Moore, Editor

EV World Open Access article originally published on July 31, 2009

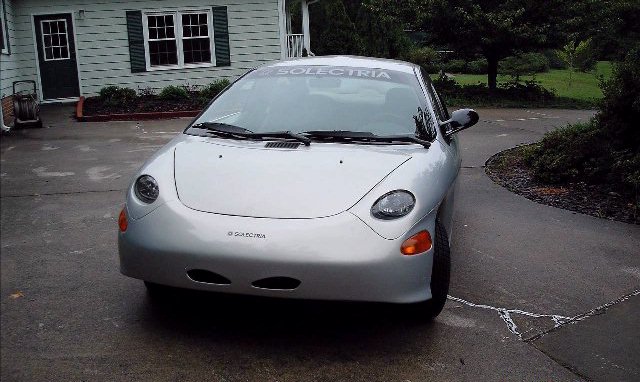

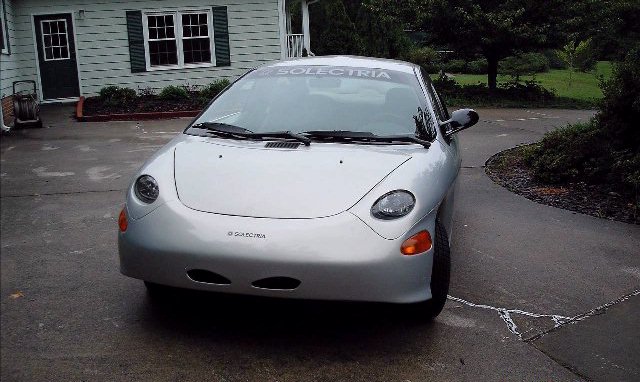

Steven Taylor's Solectria Sunrise

Will The Sunrise Again?

by Bill Moore, Editor

EV World Open Access article originally published on July 31, 2009

Steven Taylor's Solectria Sunrise

When Solectria introduced the Sunrise in 1993, it was almost perfect. In March 1995, driving a prototype Solectria Sunrise, James Worden coaxed an amazing 377 miles out of a prototype pack of Ovonic nickel metal hydride batteries. It remains to this day a feat unequaled for an electric car with nearly the same interior space as a Ford Taurus sedan of the time.

Today, only one Sunrise remains operational and is back in the hands of the man who inspired its creation in 1993.

James Hogarth was an executive with Boston Edison, responsible for managing, among other things, its electric vehicle fleet operations. His new boss, Bernie Reznicek, wasn't interested in knowing whether or not the utility should purchase electric cars. The former president of Omaha Public Power District asked, instead, were electric cars practical, were they ready? Reznicek had been hired to help clean up the financial and public relations mess caused, in part, by a 1990 study published by the Massachusetts Department of Public Health that raised serious concerns about leukemia rates around the utility's Pilgrim nuclear power plant.

Hogarth, who had long been an advocate of EVs, said yes and proposed that Boston Edison and DARPA fund the development of a state-of-the-art, five passenger electric sedan. (The two-passenger GM Impact was just then under development). He turned to James Worden, the MIT graduate who had started a small electric vehicle R&D firm called Solectria, to design and build the car. With both Boston Edison and DARPA each investing $565,000, Solectria began designing the car in November 1993.

Hogarth's instructions to Worden were to give it the same interior room as a Ford Taurus, then the best selling fleet car on the market. Hogarth's plans were to manufacture 20,000 of the composite body cars and lease or sell them to fleet operators for $20,000 apiece starting in 1997.

Thirteen months later, the car debuted -- without batteries -- at Disneyland in Anaheim during the 1994 EV Expo. Despite the presence of a dozen GM Impact production prototypes, one of which had just set the electric car land speed record of over 183 mph, the Sunrise, as it was called, was the talk of the event. Security guards alerted Hogarth during the event one evening when it was discovered that GM's Ken Baker and several other Impact engineers were scrutinizing the car from top to bottom, taking detailed photos.

By the Spring of 1995, Worden drove the Sunrise prototype the record setting 377 miles.

In recounting the history of the car for the book I am writing, Hogarth explained that Worden, who while an MIT student had driven his solar-electric car at speeds of nearly 100 mph, had a unique ability to extract the maximum efficiency out of his automobiles. [For more on the early history of the Sunrise, see excerpts from Joe Sherman's book "Charging Ahead"].

But the dream was never to be. Only a handful of the cars were ever built, one of them eventually landing in the hands of retired radio station owner Stephen Taylor of Atlanta. He bought it from eVionyx, a zinc-air battery development firm, who had hoped to use it as a technology demonstrator, but ran into technical problems with their battery.

Taylor, who has owned as many as nine electric vehicles at a time [he currently has only five] including a Corbin Sparrow and a Doran three-wheeler prototype, wanted the car as his "workhorse" to run his daughter to school and soccer practice. He purchased the car for around $25,000 and ordered some $40,000 worth of Valence lithium batteries to power it. While he waited for the batteries to arrive, he ran the car on a spare set of lead-acid AGMs, which gave the car a range of around 40+ miles. A year after buying the car, he installed 30 kWh of Valence Group 24 batteries and expected to get 300 miles of range out of the highly aerodynamic, light-weight (1,600 lb. with lead batteries) sedan. He never got any where near that, he told me.

"One hundred and fifty to a hundred and sixty miles was all I could get." The problem, he suspected, was in the 35 kWh motor that was in the car. He'd drive 50-60 miles and the motor would overheat. Frustrated, he put in an order with Azure Dynamics -- the successor to Solectria -- for a new AC drive system. Before he could take delivery, Jim Hogarth called him wanting to buy the car back.

Hogarth, now living in San Antonio, had never lost his conviction that EVs were the future and spent the next sixteen years carefully putting together a plan and a team to produce a line of efficient electric cars and trucks, largely operating in stealth mode until I called him tracking down the whereabouts of the last Sunrise. (It turns out his old boss at Boston Edison is the chairman of the company and they use the same attorneys I use here in Omaha).

He explained that his board wanted him to buy the Sunrise back so they could use it as their technology demonstrator. It is now back in Connecticut being modified by one of the same people who originally helped develop it. Hopefully, they will not only give it a new drive system but also replace the scratched rear plexiglass window that bugged Taylor. It also leaks in the rain.

Hogarth reassured me that the vehicles his company will be introducing -- once they get all their funding lined up; a common refrain these days -- is as advanced today as the Sunrise was in 1994.

In the meantime, the last unassembled Sunrise chassis is serving as a model for a future electric kit car being developed in Minnesota.

So, one way or the other, the Sunrise may come again.